Foreign policy and armed forces of Russia in the 16th – 17th centuries

Russia's foreign policy in the XVI–XVII centuries was determined by the need to eliminate external danger; the longing to expand the territory and the search for access to the shores of the Baltic and Azov seas.

One of the most important directions of the foreign policy in the XVI century was the struggle for the accession of the Volga region and mastering of the Volga trade route. Kazan campaign undertaken by Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible in 1551–1552, ended with capture of Kazan and elimination of the Kazan Khanate. The Astrakhan khanate was finally annexed in 1556. The attempt to reach the Baltic sea ended in failure: the protracted Livonian war (1558–1583) had led to catastrophic consequences.

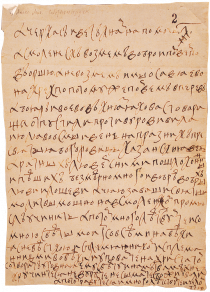

The beginning of the XVII century was a time of hard ordeal for the Russian state. The country had been shaken by peoples’ insurrections and boyar conspiracies, one after another there came imposters who claimed the Throne. The turmoil of economic and political crises was enhanced by the Polish and the Swedish interventions. The threat of loss of national independence loomed over Russia, it could have only been saved the people's liberation movement for the restoration of the integrity and national sovereignty of Russia.

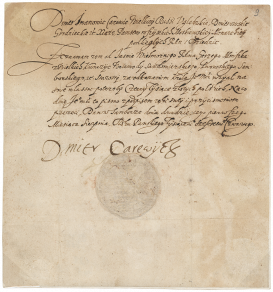

The main clot of contradictions in the foreign policy of Russia in the XVII century was the relationship with Poland. In 1632–1634 was made an unsuccessful attempt to return Russian cities captured in the Time of Troubles. In the middle of XVII century the Russian state have included the lands of Ukraine and Belorussia. Consequently, this became a reason for a new war with Poland, which ended in 1667 by a truce according to which Russia acquired the left-Bank Ukraine and regained the Smolensk and Chernihiv lands. These conditions were confirmed by the "Eternal peace" with Poland, concluded in 1686.

In 1695–1696 Peter I undertook two campaigns to seize the Turkish fortress Azov, which locked the exit to the sea of Azov. The first was unsuccessful, the second campaign supported the newly created Russian fleet, ended with the surrender of the Turkish garrison of the fortress. Constantinople peace with Turkey opened up a window of opportunities for Peter’s I active foreign policy in the new century.

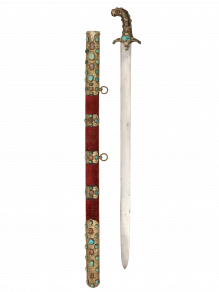

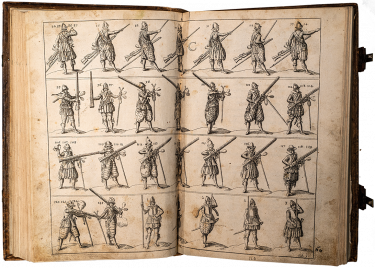

The Russian armed forces have undergone serious transformations. In the middle of the XVI century within the armed forces, the core of which was the Noble army, appeared first Strelets regiments – a prototype of a standing army. Military reforms and innovations, the mastering of the advanced practices of the European states had led to creation of so called Regiments of the New (European) system in the XVII century. This experience became a solid foundation for Peter’s I military reforms in the next century.

This hall is covered with a cylindrical vault covered with floral ornaments resembling Orental brocade. The cornice, same as in hall #20, copies the pattern of the cornices of the bell tower of Ivan the Great in Moscow Kremlin. The entrance to the hall is framed by a painted portal with an arch – a copy of the Northern entrance to the Assumption Cathedral of the Trinity-Sergiev Lavra (Monastery). On the opposite wall is a wrought iron door from the village of Pureh, the patrimony of Prince Dmitry M.Pozharsky (1578–1642), the head of the Second militia, who liberated Moscow from the Poles in 1612. The oak door leading to the marble staircase is framed by a decorative trim, the relief pattern of which is copied from a carved wooden candlestick of 1604 from the St.Demetrius Cathedral in Vladimir.

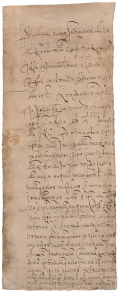

The hall is decorated with five paintings by an unknown Polish artist of the XVII century. Those paintings come from the Vishnevetsky Castle (Poland): portraits of false Dmitry I and Marina Mniszek; the engagement scene in Krakow; the entrance to Moscow and the coronation of Marina Mniszek. The last owner of the castle Kiev banker and mayor I.A.Tolly gave the paintings to the heir to the Crown Prince Alexander Alexandrovich. In 1877, the future Emperor Alexander III presented those to the Historical Museum. During the initial design of the hall, special niches were provided for these paintings.

In 1936 the hall was reconstructed: the stucco was knocked down; the painting was whitewashed; the canvases were moved to storage room. In the mid-1980s reconstruction works were done.